Date Posted, by Jack J. Lee, Ph.D.

Overall, cancer death rates in the United States have been declining about 2% per year, current SEER data from 2014 through 2018 show. However, these improvements have not been experienced equally by everyone, which is one of the reasons that April is Minority Cancer Awareness Month, when we call attention to these disparities.

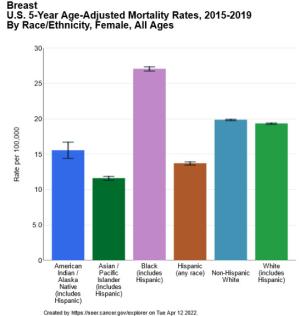

Black women in the United States are more likely to die from breast cancer than women of other racial and ethnic groups, a new risk tool estimates. American Indian and Alaska Native people have much higher rates of getting certain cancers, such as liver and stomach cancers, compared to non-Hispanic White populations, CDC reports. In addition, people who live in U.S. counties that experience persistent poverty are more likely to die from cancer than people in other counties, an NCI study found.

Precision medicine could improve these gaps. This emerging approach, which includes precision cancer prevention, provides personalized recommendations based on a person’s genetic makeup, behaviors, and environment. Focusing on biological factors while overlooking social factors, however, could potentially worsen existing imbalances.

“We must be careful that we don’t exacerbate existing disparities by inadvertently creating inequitable access to interventions between communities,” said Eboneé Butler, Ph.D., an assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Butler coauthored a review with members of NCI’s Division of Cancer Prevention (DCP) recommending a broader framework for precision cancer prevention to promote health equity. The study proposes the following definition that unambiguously includes nonbiological factors: “Precision cancer prevention is the equitable provision of a targeted, preventive intervention to mitigate one or more biological, demographic, or social determinants of cancer risk while minimizing its harm.”

“Understanding social determinants of health helps us refocus our attention to the communities where people live day-to-day and helps us think critically about how community context contributes to cancer risk,” Dr. Butler said.

Social determinants of health are considered the conditions that people experience where they live, work, and play. Some examples are education, availability of healthy food, safe housing, discrimination, pollution, and healthcare access. These factors influence personal cancer risk. Lack of access to healthy foods, for example, is associated with obesity, which has been linked to increased risks of at least 13 types of cancer.

Breast U.S. 5-Year Age-Adjusted Mortaility Rates, 2015-2019 by Race/Ethnicity, Female, All Ages

| Race/Ethnicity | Rate per 100,000 |

|---|---|

| American Indian / Alaska Native (includes Hispanic) | 15.6 |

| Asian / Pacific Islander (includes Hispanic) | 11.6 |

| Black (includes Hispanic) | 27.1 |

| Hispanic (any race) | 13.7 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 19.9 |

| White (includes Hispanic) | 19.4 |

The goal of the review is to encourage researchers to consider a holistic approach to cancer prevention, Dr. Butler said, and to better understand and acknowledge the people and communities they wish to serve.

Reflecting the Entire Population

Another issue to be addressed is that precision medicine interventions may not be equally informative or effective for all people. For example, the Oncotype DX test, which guides treatment decisions for women with early stage breast cancer based on gene activity in the tumor, is less accurate for Black women than for non-Hispanic White women. This discrepancy may be because the test was developed and validated using samples from studies that enrolled relatively few Black women.

“Clinical assays are often validated in research populations that do not reflect patient diversity. This impacts our ability to develop prognostic assays that cover the breadth and depth of disease course in all populations,” Dr. Butler said.

Similarly, human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines prevent viral infections that cause cancer but may provide different levels of benefit. All current vaccines target the virus types responsible for most HPV-caused cancers, HPV16 and HPV18. However, they don’t target HPV35, which causes more cervical precancer and cancer in Black women than in White women. Studies are needed to determine whether adding HPV35 to existing vaccines provides better protection for women in Africa or of African ancestry.

Improving Access

An additional consideration is how and where precision medicine interventions are delivered.

The standard of care today recommends that newly diagnosed advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients who may be candidates for first-line treatment with an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor receive molecular testing of tumors for EGFR gene mutations. A 2018 study, however, uncovered widespread underutilization of EGFR testing by Medicare patients. The researchers identified racial, income, and regional disparities, with Medicaid status being the factor most correlated with a lack of testing. These results suggest that those with limited income have reduced access to lung cancer molecular tests.

New delivery strategies could help. In a report published in February 2022, the President’s Cancer Panel recommended self-sampling approaches for increasing access to cancer screening. Though self-sampling for HPV testing has not yet been approved for use in the United States, research has shown that accuracy of HPV testing on self-collected samples is similar in most cases to that of samples collected by a clinician. Such self-sampling also has been implemented in other countries.

DCP is leading the NCI’s Cervical Cancer “Last Mile” Initiative, a public-private partnership that will conduct a clinical trial to validate HPV testing with self-collected samples for cervical cancer screening in the United States.

“Our efforts are geared to inform the regulatory approval process and provide actionable evidence for expanding self-sampling-based cervical cancer screening to underserved and under-screened communities,” said Vikrant Sahasrabuddhe, Dr.P.H., M.B.B.S., a program director for the DCP Breast and Gynecologic Cancer Research Group.

A More Holistic View

A broader framework for precision cancer prevention will improve how we design and implement large-scale studies, Dr. Butler said. In particular, a more holistic view could help in teasing apart how biological and social factors each contribute to health inequities.

“The promise of an equitable society is often considered to be a far-off future goal. But my hope is that we begin to realize that goal today by prioritizing equitable access to existing interventions. Achieving equity will lead to an improved understanding of cancer etiology, which in turn will highlight additional targets for cancer prevention,” Dr. Butler said.

References

Butler EN, Umar A, Heckman-Stoddard BM, et al. Redefining precision cancer prevention to promote health equity. Trends in Cancer 2022; 8(4): 295-302.

Loomans-Kropp HA, Umar A. Cancer prevention and screening: the next step in the era of precision medicine. NPJ Precis Oncol 2019; 3: 3.

Lord BD, Martini RN, Davis MB. Understanding how genetic ancestry may influence cancer development. Trends in Cancer 2022; 8(4) 276-279.

Lynch JA, Berse B, Rabb M, et al. Underutilization and disparities in access to EGFR testing among Medicare patients with lung cancer from 2010 - 2013. BMC Cancer 2018; 18(1): 306.

If you would like to reproduce some or all of this content, see Reuse of NCI Information for guidance about copyright and permissions. Please credit the National Cancer Institute as the source and link directly to the blog post using the original title, for example: "How Precision Cancer Prevention Can Promote Health Equity was originally published by the National Cancer Institute." For questions, contact us at CancerPreventionBlog@mail.nih.gov.