Date Posted, by Susan Jenks

In a clinical study underway, scientists hope to unravel the complexities of a group of poorly understood and relatively rare blood disorders that often lead to cancer. In myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), the problem arises when normal blood cells fail to function properly or are ill-formed inside the spongy bone marrow where blood production begins, leaving patients vulnerable to infection, anemia or easy bleeding.

Dr. Mikkael Sekeres

“These are probably the most common myeloid (bone-marrow related) malignancies we see, but we know little about their natural history,” said Mikkael Sekeres, M.D., chairman of the MDS study and chief of the Division of Hematology at the University of Miami Health System Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center. “Our understanding is pretty primitive.”

Studying the Natural History of MDS

To address the research gap, The National MDS Study (NCT02775383) aims to create a publicly available database from the blood and tissue samples of patients with newly diagnosed MDS or with closely related disorders. The national biorepository, housed at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, will enable research scientists to track genetic and chemical changes that occur in red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets as MDS progresses towards worsening disease—a strategy that may lead to prevention or earlier, potentially more effective treatments in the future.

Since the study began in 2016, some 1,400 patients have been enrolled. Doctors first must confirm each diagnosis through a bone marrow biopsy.

“Patients have to be enrolled before they get MDS, before they undergo a bone marrow biopsy,” Dr. Sekeres stressed. “Although we’ve been able to do it, so far recruitment is expected to take at least two more years to meet the goal of 1,750 participants. Hence , the investigators are working to promote the study to accelerate accrual. Also, the investigators want to attract a higher percentage of minority patients to better reflect their numbers in the general population and prevalence of the disease.

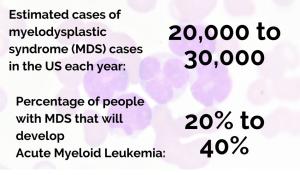

National MDS Study, jointly sponsored by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) is an observational study to understand the natural history and management of those who do and do not progress to leukemia or other diseases. Investigators hope through frequent and well-characterized blood draws and tissue samples from patients, they will gain not only a clearer understanding of the many subtypes in this disease, but also settle a lingering controversy over the extent of MDS’ role in malignancy. The World Health Organization classifies these blood disorders as cancers, but some estimates suggest about 20% to 40% of patients will develop acute myeloid leukemias, the blood cancer associated with it. Others presumably die of competing risks and diseases, common in the older age groups most vulnerable to these disorders.

At study entry, participants are identified as either high-risk or low-risk MDS patients after their confirmatory biopsies, and divided into different cohorts. Those individuals deemed high risk are consid-ered the most likely to develop leukemia, according to Dr. Sekeres. “Loosely defined,” he said, “these individuals have more lab abnormalities, worse genetic profiles and a higher percentage of blasts”—immature white blood cells that rapidly divide, crowding out other blood cell types in the bone marrow. Once blast counts dwarf normal blood cells, doctors diagnose outright leukemia.

“The most worrisome aspect of MDS is this ability to transform into leukemia,” said Salil Goorha, M.D., an oncologist at Baptist Memorial Hospital in Memphis, and one of the study’s principal investigators. Why someone at low risk for leukemia goes on to develop one of these blood cancers is “something we don’t quite understand,” he said, and one of the obvious reasons for the ongoing study.

Improving MDS Treatment and Detection

Myelodysplastic syndromes are diagnosed in an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 people in the United States each year. But, that number is expected to rise as the population continues to age because age alone is a well-known risk factor for MDS. So too is exposure to certain chemicals, or prior chemotherapy treatments for other cancers, which account for roughly 5% to 10% of cases.

Dr. Salil Goorha

Other causes remain unknown. MDS treatments, which are tied to disease severity, offer mostly palliation, with only stem-cell transplants holding a potential for cure. Even then, investigators say, fewer than 5% of patients qualify to receive healthy bone marrow from a matched donor.

With such a clear need for advances in both basic research and innovative treatments, the MDS study will follow those who choose to enroll at least 6 months, but perhaps their entire lifetime. “It’s open-ended for now,” Dr. Sekeres said, referring to the study time frame, as physicians from the NCI National Clinical Trials Network and NCI Community Oncology Research Program continue to encourage patients from around the country to participate.

By digitizing data gleaned from patients’ bone marrow and processing it through artificial intelligence, Dr. Sekeres said, physicians may be able to diagnose MDS far earlier than is currently possible. Images produced by AI technology can detect signs of early molecular changes in the marrow invisible to the human eye, providing possible genetic targets for clinical intervention.

“A lot of genetic abnormalities are seen in MDS, or are associated with MDS,” Dr. Sekeres said, “but nothing is specific yet.” The hope is the creation of a national resource, such as this, will give scientists a clearer molecular window on the disease that will help MDS patients in the future, he said.

If you would like to reproduce some or all of this content, see Reuse of NCI Information for guidance about copyright and permissions. Please credit the National Cancer Institute as the source and link directly to the blog post using the original title, for example: "Study Seeks to Unravel the Complexity of Rare Blood Disorders Known as Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) was originally published by the National Cancer Institute." For questions, contact us at CancerPreventionBlog@mail.nih.gov.