Date Posted, by Jack J. Lee, Ph.D.

Unlike many other cancers, the incidence and death rates for uterine cancer are rising.

An example of a nonendometrioid cancer.

Rates of new uterine cancer cases have risen 0.6% per year from 2010-2019, and death rates have risen an average of 1.7% per year for the same time frame.

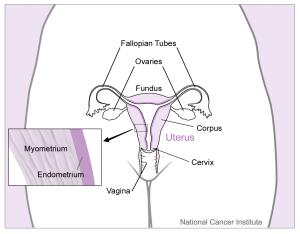

Over 90% of uterine cancers begin in the endometrium, the tissue lining the uterus. There are two main subtypes of endometrial cancer, endometrioid and nonendometrioid, and the subtypes are showing different trends, a recent NCI-led study found.

The researchers tallied endometrial cancer deaths in the United States from 2010 to 2017, accounting for hysterectomy prevalence. Deaths from endometrioid tumors remained steady. However, the death rate from the aggressive nonendometrioid tumors rose by 2.7% each year.

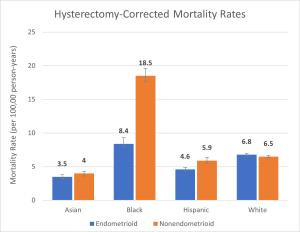

The analysis also underscored racial disparities: Black women consistently had worse outcomes for both subtypes than other women.

The NCI Division of Cancer Prevention (DCP) is addressing these issues by supporting gynecologic cancer prevention research and developing concepts for future studies.

“DCP is committed to expanding our portfolio in that space,” said Goli Samimi, Ph.D., M.P.H., program director in DCP’s Breast and Gynecologic Cancer Research Group.

On This Page

- All Headings will automatically be pulled in to this list.

- Do not edit the content on this template.

Hormones and the Endometrium

High levels of estrogen can lead to thickening of the endometrium. This overgrowth can progress to form endometrioid tumors, which account for about 80% of endometrial cancers.

Analyses of biopsied tissue can determine if abnormal growths appear to be precancerous. For such endometrial precancers, experts recommend hysterectomy. The surgery completely removes the uterus and cervix. But some women may still want to have children, while others may not even be eligible for surgery. Obese individuals, for example, may face high risks for surgical complications.

Another option is to treat endometrial precancer or low-grade cancer with progesterone. Progesterone counters estrogen during the menstrual cycle. It plays a key role in shedding of the endometrial lining. Treatment with progestin, a synthetic version of the hormone, can shrink the abnormal growths in the endometrium.

“But it doesn’t work perfectly,” said Emma Barber, M.D., a gynecologic oncologist at Northwestern University. For example, a previous systematic review of outcomes in women diagnosed with endometrial precancer found that only about 65% had complete response to progestin treatment during the study periods. In women with grade 1 endometrial cancer, only 48% had complete response. Additional non-surgical treatment options for women with endometrial precancer and endometrial cancer could provide improved response.

A cross section of the female reproductive system highlighting the endometrium

The endometrium is the tissue lining the uterus; there are two main subtypes of endometrial cancer showing difference rates of changes; one is steady, and the other is rising.

A “Window of Opportunity”

Dr. Barber is leading a trial, funded by the DCP Cancer Prevention Clinical Trials Network (CP-CTNet) to see if metformin improves progestin’s ability to prevent endometrial progression. Metformin is commonly prescribed to control diabetes. It has also been shown to have anti-cancer properties.

The Megestrol Acetate Compared with Megestrol Acetate and Metformin to Prevent Endometrial Cancer trial is a “window of opportunity” study. Following a diagnosis of endometrial precancer, participants scheduling hysterectomy for treatment will be contacted to consent and enroll in the trial. The investigators will make a baseline measurement of cell proliferation using tissue from the biopsy that was taken for diagnosis. Then the women receive one of two drug regimens for 3-5 weeks before their surgery: half take progestin alone, the other half take progestin and metformin.

After surgery, investigators can analyze the removed precancer and calculate changes in cell proliferation. The study will allow investigators to compare how the two treatments affect endometrial growth.

Dr. Barber presented information about the trial at the I-SCORE meeting in March 2022. At that time, five women had enrolled in the study. Though participants may not directly benefit from the study findings, they still want to help other women, all while facing tough situations themselves. “We have really great patients,” Dr. Barber said.

An Approach that Blocks Estrogen Production

Another DCP-supported trial is investigating a different treatment for endometrial precancers. This study is evaluating an aromatase inhibitor, a drug that blocks the production of estrogen.

The Exemestane in Treating Patients with Complex Atypical Hyperplasia of the Endometrium/Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia or Low Grade Endometrial Cancer trial is also a window of opportunity study. All participants have a diagnosis of either low-grade endometrial cancer or precancer and ultimately undergo standard-of-care hysterectomy. They receive oral medication in the weeks preceding surgery. The investigators are measuring changes in cell proliferation before and after surgery.

In this trial, the investigators are studying if exemestane causes regression of endometrial cancer or precancer. This aromatase inhibitor is commonly used in treatment of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer treatment and maintenance therapy. Because estrogen drives the proliferation of endometrial cancers and precancers, blocking estrogen production may have a positive affect on endometrial tumors.

“We’re hopeful because this is a more advanced generation aromatase inhibitor,” said Britt Erickson, M.D., a gynecologic oncologist at the University of Minnesota. She is also the principal investigator for the trial. Exemestane may cause fewer side effects than drugs developed earlier, Dr. Erickson said.

The study recently completed accrual and analyses are underway.

In addition to studying changes in the endometrium directly, the study scientists are also studying cells that were obtained from participants through vaginal tampon collection. Differences in protein and genetic markers in these cells will be studied to see if they could predict response to the drug. “We’re looking to see if there are clues in the cells,” Dr. Erickson said. In the future, this information could guide personalized treatments for endometrial precancer and low-grade cancer.

Like the previous trial, these women are really helping other women. “It’s really impressive to see that they seem very willing to participate in these studies,” Dr. Erickson said.

Investigating Molecular Differences

The second subtype of endometrial cancer, nonendometrioid tumors, make up about 20% of endometrial cancers in the United States. But they account for over half the deaths.

Hysterectomy-Corrected Mortality Rates

| Race and Ethnicity | Endometrioid | Nonendometrioid |

|---|---|---|

| Asian | 3.5 | 4.0 |

| Black | 8.4 | 18.5 |

| Hispanic | 4.6 | 5.9 |

| White | 6.8 | 6.5 |

Mortality rates are hysterectomy-corrected and expressed per 100,000 people per year.

There are also racial disparities with nonendometrioid cancers. An earlier NCI study reported that Black women have had higher incidence of the aggressive subtype than women of other racial and ethnic groups. The team’s recent study found that the death rates for nonendometrioid cancers are twice as high for Black women than other women. Further, the death rates grew for all women from 2010 to 2017. Hispanic, Black, and Asian women experienced the biggest increases.

Scientists have made progress identifying molecular differences between endometrial tumor subtypes. But most of the specimens analyzed in these studies came from White women. Broader conclusions will need more diverse participants and samples.

“Black women and their tumors have been underrepresented in most of the large genomic profiling studies,” said Victoria Bae-Jump, M.D., Ph.D., a gynecologic oncologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. She is co-leading a large effort with UNC epidemiologists Hazel Nichols, Ph.D., and Andrew Olshan, Ph.D., to address this gap.

The Carolina Endometrial Cancer Study is seeking 1,800 women across the state of North Carolina from all 100 counties, Dr. Bae-Jump said. The investigators are aiming for 50% of the women enrolled to be Black women. They want to analyze their endometrial tumors to identify genetic details. Such molecular information could guide therapeutic strategies.

The team also wants to get a fuller picture of the women’s experience. All the study participants will be interviewed. This data will enable analyses on social demographic factors.

Dr. Bae-Jump’s group is also developing mouse models based on endometrial tumors from Black women, as very few exist. These studies could provide insight into differences in cancer progression. Additionally, Dr. Bae-Jump is studying metabolic and molecular biomarkers of endometrial cancer through an R37 MERIT Award. This award provides additional funding for early-stage investigators.

“We’re really trying to look at all the reasons together of why we have this terrible disparity for Black women,” Dr. Bae-Jump said.

References

Clarke MA, Devesa SS, Harvey SV, et al. Hysterectomy-Corrected Uterine Corpus Cancer Incidence Trends and Differences in Relative Survival Reveal Racial Disparities and Rising Rates of Nonendometrioid Cancers. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2019; 37(22): 1895-1908.

Clarke MA, Devesa SS, Hammer A, et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Hysterectomy-Corrected Uterine Corpus Cancer Mortality by Stage and Histologic Subtype. JAMA Oncology 2022.

Gunderson CC, Fader AN, Carson KA, et al. Oncologic and reproductive outcomes with progestin therapy in women with endometrial hyperplasia and grade 1 adenocarcinoma: a systematic review. Gynecologic Oncology 2012; 125(2): 477-482.

Ko EM, Walter P, Clark L, et al. The complex triad of obesity, diabetes and race in Type I and II endometrial cancers: prevalence and prognostic significance. Gynecologic Oncology 2014; 133(1): 28-32.

Lawrence WR, McGee-Avila JK, Vo JB, et al. Trends in Cancer Mortality Among Black Individuals in the US From 1999 to 2019. JAMA Oncology 2022.

Lu KH, Broaddus RR. Endometrial Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2020; 383(21): 2053-2064.

If you would like to reproduce some or all of this content, see Reuse of NCI Information for guidance about copyright and permissions. Please credit the National Cancer Institute as the source and link directly to the blog post using the original title, for example: "Rising Endometrial Cancer Rates Spur New Approaches to Prevention was originally published by the National Cancer Institute." For questions, contact us at CancerPreventionBlog@mail.nih.gov.