Date Posted, by DCP Staff

If your family member had cancer, would you want to know if you carried a gene mutation that increased your risk of the same cancer? This question is at the heart of three novel research projects underway to determine how best to connect with the family members of women with ovarian cancer so they can decide whether to get genetic testing and counseling about their own risk of cancer.

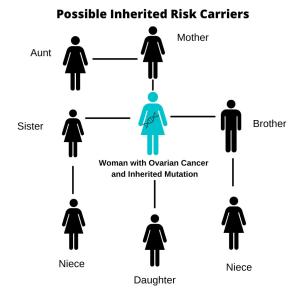

Possible Inherited Risk Carriers

The strongest risk factor for developing ovarian cancer is an inherited genetic mutation being passed from generation to generation, most often a mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene. A family with an inherited gene mutation can have multiple first-degree relatives diagnosed with cancer.

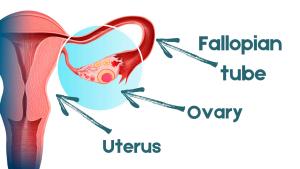

In the general population, a woman’s lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer is about 1.2% But if she carries hereditary mutations in either the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, the risk for developing ovarian cancer before age 70 years jumps to 11% to 40%. Currently, the only preventive option available involves the removal of both ovaries and the fallopian tubes (salpingo-oopherectomy), a procedure which can decrease the risk of developing ovarian cancer by an estimated 98%.

Gynecologic oncologists recommend that most women diagnosed with ovarian cancer be referred for risk assessment and genetic testing. If they are found to have an inherited genetic mutation, testing their first-degree relatives provides an opportunity to reduce the risk of ovarian and other cancers in those who also may have inherited the mutations. Although current guidelines call for women diagnosed with ovarian cancer to undergo genetic testing, at least one national study suggests as few as 10% follow this recommendation.

“What happens is women are getting diagnosed with ovarian cancer, but they’re not getting tested,” said Goli Samimi, Ph.D., M.P.H., program director in the Breast and Gynecologic Cancer Research Group in the NCI Division of Cancer Prevention. “Some succumb to their disease, others don’t want to be tested, so their daughters, nieces and sisters turn up in clinics later with a cancer diagnosis carrying BRCA mutations. It is a missed opportunity for cancer prevention.”

Testing a “Traceback” Strategy

NCI released a funding opportunity to test a “traceback” strategy, where researchers are finding the women who were previously diagnosed with ovarian cancer, communicating with them (or with their family members if they have died), and offering genetic testing. Traceback is a unique approach to genetic testing because the idea is to work backwards and find previously diagnosed cases to test to improve the detection of families at risk.

Three grants using different approaches for traceback testing were funded for 4 years; projects are expected to be completed in 2023. The overall goal is to evaluate the best way to communicate sensitive genetic information to ovarian cancer patients and their immediate family members. Challenges associated with privacy laws and ethical concerns, differences in cultural traditions, and medical literacy are taken into account.

The Kaiser Foundation Research Institute is analyzing medical records to identify previously diagnosed ovarian cancer cases within the past 10 years. They are selecting patients who have not had genetic testing or who have been tested only for BRCA1/2 mutations, but not the full panel of genes commonly associated with ovarian cancer. The project includes both living and deceased women—a strategy that potentially could inform close family members of their own risk, even when a relative has died.

See also

Posted: 09/07/2021

“The more families we can identify, the more that can be done to prevent or catch these cancers early” in at-risk individuals, said Jessica Hunter, Ph.D., a genetic epidemiologist and principal investigator of the Kaiser grant. So far, she said, medical records for 600 women have been identified through tumor registries at two sites, Kaiser Permanente Northwest and Kaiser Permanente Colorado. About half of them died of ovarian cancer.

Before contacting the relatives of those who died or survived ovarian cancer, the research team spent a year reviewing regulatory and legal issues surrounding whose permission might be needed to share private medical information. To date, no information has been imparted to the families of deceased patients, Dr. Hunter said, although responses have been “quite nice” from family members of ovarian cancer survivors who agreed to genetic testing and tested positive for BRCA1/2 mutations.

“We contacted as many family members as possible—daughters, siblings, sons and even brothers,” Dr. Hunter said. “We included them (brothers) because they could be at risk for a cancer of their own, but also have daughters at risk for ovarian cancer.”

Using another tactic, researchers at the Geisinger Clinic deal only with the medical records of ovarian cancer survivors. The project focuses on communication strategies that use culturally appropriate language to inform women about the availability of genetic testing. The long-term goal is to determine the feasibility of traceback testing as “both practical and sustainable in the real world.”

Finally, researchers at Emory University are partnering with the Georgia Cancer Registry and community cancer organizations to identify ovarian cancer survivors and their relatives, and to conduct interviews to determine how best to communicate personal genetic information and the results of genetic testing. This type of message-based outreach could eventually be compared in clinical studies with standard approaches for conveying personal cancer risk to determine which one is more effective.

If you would like to reproduce some or all of this content, see Reuse of NCI Information for guidance about copyright and permissions. Please credit the National Cancer Institute as the source and link directly to the blog post using the original title, for example: "Studies Focus on Testing Family Members of Cancer Gene Carriers was originally published by the National Cancer Institute." For questions, contact us at CancerPreventionBlog@mail.nih.gov.